Trinity Church, (Beaver, PA)

2/15/11

Matthew 5-7

"Be Ye Perfect (or Complete, or Mature)..."

Every

December 24th my family—on my mother’s side—comes together to

celebrate the holidays. Only we don’t

actually celebrate Christmas. Instead, being

good Reformed/agnostic Jews, we celebrate each other’s company and catch up on happenings

of the past year. We eat potato latkes,

listen to Hanukkah songs, and say “uh vey” quite a bit. I always look forward to Christmas Eve, for

it never fails to be my favorite day of the year.

With

that said, my family is a loud and opinionated bunch—and I wouldn’t have it any

other way. They’ve got their opinions on

sports, celebrities, and fashion, but they save their most passionate speech

for issues of politics. You see I’m from

New Jersey, and in Jersey most people are pretty liberal. Being fairly politically apathetic myself, I

enjoy hearing my family rant about health care, the war, and especially Sarah

Palin because—quite frankly—it’s entertaining.

My

family is concerned about great things.

They hope to see the poor no longer go hungry, they hope to see peace

reign supreme, and they hope to see bipartisan polarization extinguished. And while all these are good things,

something always bothered me about the way we talked about these things. And I couldn’t put my finger on what it was until

I read a book by the Catholic novelist Walker Percy called The Moviegoer.

In

this story, a man by the name of Binx Bolling sets out on a search, but for

what, not even he knows. All he knows

for sure is that not to be “on the search” is to be in despair. While on this quest he decides to listen to

the 1950’s radio show “This I Believe” thinking maybe he’ll find something

there. It’s his discovery here that

helped me understand what was so disappointing about the way my family would

talk about such good things.

The

book reads this way:

“On

This I Believe they like everyone. But

when it comes down to this or that particular person, I have noticed that they

usually hate his guts.” (pg 108-109)

Or

in the case of my family, they usually hate Sarah Palin’s guts.

Now

I’m not by any means advocating conservative politics. I have more than a fair share of conservative

friends who hate Barack Obama’s guts, and I am just as disappointed by their

rhetoric. I raise this point only in an

attempt to illustrate our Gospel lesson this morning. You see, my family and I are often times guilty of being “lovers of humanity” or lovers of an abstraction. Fyodor Dostoyevsky put it this way, “The more I

love mankind in general, the less I love people in particular.” When it comes

to loving individual persons, I tend to be mostly unsuccessful. Most days, I love only those who love me.

So

when I read verses 43-45 of the fifth chapter of Matthew, I feel

convicted. For Jesus says, “You have heard that it was said, 'You shall love your

neighbor and hate your enemy.' But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for

those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in

heaven.” And as if to throw it in my face, he further adds, “For if you love [only] those who love you, what reward do you have?” In this passage Jesus exposes

me for the “lover of humanity” that I am.

But if you’re like me, you’re wondering what does this text

mean? I admitted that I was convicted that I only love those who love me, but what does it even mean to love your enemies and your persecutors? I want to find a way to soften the

rough edges, to dissect the command and analyze it in such a way that it becomes

depersonalized. So first I focus on the

word “love” which in Greek is the familiar agape. I think to myself, “Alright this might be

doable, because agape love is

dispassionate. That means I pray for

them, do good to them, and greet them, and, therefore, I am loving—agape-ing—my

enemies."

But as I think things through I begin to realize that it’s not

quite that simple. First, the Greek noun

and verb for agape are often times

used to describe human affections and desires.

Second, in I Corinthians 13:3, St. Paul writes, “If I give all I possess

to the poor and surrender my body to the flames, but have not love, I gain

nothing.” St. Paul is addressing

attitudes of the heart, and not just outward deeds. My attempt to soften the rough edges has

failed. Despite my finagling, this love

for enemies includes inward attitudes not just outward deeds.

Hoping that relief is around the corner, I read a little

further. Verse 46 reads this way, “For if

you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the

same? And if you greet only your

brothers, what more are you doing than others?

Do not even the Gentiles do the same?” Almost needless to say, my quest for relief has been negated. In this verse, Jesus is essentially telling me that I am no better than a tax

collector or a Gentile, and based on the Jewish attitude toward these two

groups in the Gospels, it would appear that my “love for humanity” is being

compared to that of the dirty and despised sinners.

Yet again, no relief for my troubled soul.

So I continue on which brings me to verse 48, what most scholars view as the climax or

summit of the Sermon on the Mount. And it goes like this, “You therefore must

be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”…

And maybe it’s just me,

but most times I read this verse I fall into no small depression. “Be perfect as my Father in heaven is

perfect?” How is that even thinkable, let alone possible?

So once again I do what I do best, I try to soften the rough

edges. I try to dissect and analyze the text so that the offense of the verse is

removed. So appealing to the Greek once

again I notice that it is possible for the Greek word for “perfect” to mean

“complete” or “mature,” and not “sinless.”

I think to myself, “This might be manageable after all”…

But after I take a closer

look, I realize that even if the word did not somehow mean “sinless” in this

context, it is hardly a relief. For when

I substitute “complete” or “mature” in the place of “perfect,” I realize that

the demand has not been loosened; the goal is still not within reach. For no matter how hard I try I could never be

as “complete” or “mature” as the Father in heaven is “complete” or ”mature.”...

Once again my finagling with the text leads

me nowhere...

So how, then, do we take this text seriously? How does someone become “perfect” as their

Father in heaven is “perfect?” The text

makes the ideal sound as if it’s unattainable.

And I think it is. At least, I think it is for us.

With that said, while I’ve never met perfect person, I have caught

brief glimpses of true, selfless love. And

I’m sure that you have too. Maybe you’ve

seen it in the radical, unmerited love of a father who’s received his wayward

son after the seventh incarceration. Or maybe

you’ve seen it in the wife who stands by her man despite the fact that he’s

been in a coma for 15 years. Or maybe you've witnessed this type of selfless love in a much less dramatic setting. Either way, we’re

captured by these glimpses, these instances of grace, because there is so very

little of it in this life.

At times, we

see it in our favorite movies, or read about it in a favorite books and it’s

enough to melt our hearts. It’s enough

to elicit belief in a merciful God—a God who calls his enemies, you and me, his

Beloved.

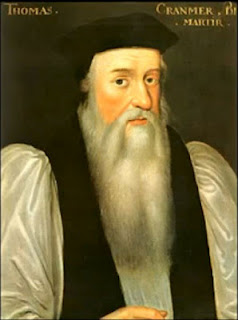

As one who’s spent a greater part of his life reading history

textbooks, I would occasionally catch glimpses of this selfless love in the

lives of characters of the past. One of

my favorite examples is the latter part of our very own Thomas Cranmer’s life.[1] Far from perfect, the author of the first Book of Common Prayer committed himself to loving his enemies during a time of

religious and political upheaval. He

made this vow because—reading this passage and others—he came to believe that

that the highest expression of divine love is to love one’s enemies.

At a time when the nation was transitioning

to a more Protestant form of religion, Cranmer was the Archbishop of Canterbury—the

head of the Church of England. He had

many enemies, many of these former friends who were now doing everything in

their power to take him down and have him killed.

At a time when the nation was transitioning

to a more Protestant form of religion, Cranmer was the Archbishop of Canterbury—the

head of the Church of England. He had

many enemies, many of these former friends who were now doing everything in

their power to take him down and have him killed.

On numerous occasions King Henry VIII—when he wasn't out finding

wives—would scold Cranmer for not taking measures against enemies—against those

who tried to have him killed. But

Cranmer was committed to loving his enemies giving second, third, and fourth

chances. And this is because radical

forgiveness was the foundation of his theology.

But Cranmer—as good a guy as he was—did not try to dull the sharp edges of our Gospel lesson. Cranmer was smart enough to know that he did

not love with a selfless love. He knew

that he could never be complete as his Father in heaven is complete.

Nonetheless, Cranmer believed in a good God, a merciful God, who

loves the imperfect, the sinner, even the God-hater. Cranmer knew that if the highest expression

of divine love is to love one’s enemies—the summit of the Sermon on the

Mount—that must be the very same kind of love by which God saves sinners.

But this idea is not original to Cranmer, for this is the exact

same thing St. Paul writes in Romans 5:10: “When we were enemies, we were

reconciled to God through the death of his Son.”

God loved you and me when we had not a right to be loved. Jesus—the God-man—lived the perfect life that

we could not live to save us. To give

his people his righteousness, his holiness, his perfection and to take their

sins upon himself on the Cross so that as 2 Corinthians states, “He became sin

who knew no sin that we might become the righteousness of God.”

So when we read the beginning of our Gospel lesson—and the Sermon

on the Mount as a whole—we realize that a great exchange has occurred. For when we look at the imperatives of verse

39ff. (please follow me as I run through this) we realize that Jesus turned the other cheek at his

trial. At Golgotha Jesus freely gave up

his tunic and cloak. When forced to go

one mile with the Cross, despite his lack of strength Jesus went “two.” Jesus gave and did not refuse the one who

begged from him. Finally, Jesus loved us

while we were sinners, rebels, God-haters.

As he was being raised on the Cross and was about to die, he prayed for

his enemies, and his enemies were not just the Roman soldiers or the Jewish

Sanhedrin, but also you and me. For our

sins put him up there too. Yet he loved

us so much that at the height of his agony, he did not curse us but instead prayed for us saying,

“Father forgive them for they know not what they do.”

Jesus was perfect as his Father in heaven is perfect. Jesus is

the only person to ever fulfill verse 48. Yet instead of keeping his merit,

his perfection, to himself—as he had every right to do—he gave it to you and me

in exchange for sin.

Therefore, you and I have already fulfilled all of the demands of

the Sermon on the Mount. We have turned

the other cheek, we have given our tunic and our cloak, we have willingly gone

the two miles instead of one, we have given freely to the one who begs from us,

we have loved our enemy and prayed for those who’ve persecuted us… Finally, we

have been perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect, because Jesus’

accomplishments have been given to us.

You see, the Sermon on the Mount is first and foremost about

Jesus, for only he could fulfill the demands of the Law…

Verse 2 of our Old Testament lesson reads, “You shall be holy, for I

the Lord your God am holy.” By his life,

death, and resurrection we have been made holy.

Jesus Christ lived these laws perfectly and instead of keeping the merit

for himself, he has decided to credit it to you and me. Therefore, despite our sin, you and I are holy

as He is holy.

So what does this mean?

This means that through the gift of faith that we have been given, you

and I are in right standing before God despite our shortcomings. You and I have been bought with the blood of

the lamb, and, because of this, we are saved.

We are safe.

Therefore, repent and know that his promises are sure, for he is

not fickle like you and me…

But what then are Christians to do, you ask? If Jesus has taken care of righteousness and

holiness for us, what left is there to do?

The answer is that you are to rest in the love of Christ, knowing that

his love is unconditional.

Unfortunately, we humans are neurotic beings. And that means that you’re probably going to

need to be reminded of this great news weekly, daily, hourly, because twenty

minutes from now all of you will find it too good to be true. And you’ll find a way to convince yourself

that if I try really, really hard, I’ll be able to be perfect as my Father in

heaven is perfect.

You will, like me, try to soften those rough edges to make these

commands manageable. You’ll start talking about how God doesn’t actually expect

perfection. I mean he’s reasonable, right? And you’ll forget that these unattainable

commands are meant to humble you by showing you how far short you fall of what

the Law requires...

Therefore, when the temptation to loosen the demands of the Law arise—and

you find yourself believing that God could never love a sinful person like yourself—reject this foolishness and grab a hold of the Cross again. For yes, you are a sinner, but you are a

sinner who’s been deemed a saint.

Finally, as the Gospel seeps into your veins and you begin to

understand that you truly are His Beloved, know that you are invited to live

into your new reality. You are invited

to love your enemies like Thomas Cranmer did.

You are invited to no longer be the dog who continually returns to his

own vomit.

And as you attempt to live into your new reality, know that you

will continue to fall short, but that when you do fall short you are not

condemned, for you have been covered in the righteous robes of Christ.

No comments:

Post a Comment